A False Dawn by Jason Fung; The Cancer Code

This post will be in two parts, both of which I find are illustrative of the difficulties of public health strategies. One makes particularly obvious the severe misanthropic consequences of profit seeking drives in the areas of health and medicine, and the second is a remarkable case point in the iatrogenic potential of public health interventions which may be completely benevolent in intention – something that all states irrespective of political structure must address. Part one is contained below, you can find part two (here)[]

I encourage everyone to read the entirety of Jason’s “The Cancer Code”. It’s a terrific work of ‘popular’ scientific writing, as much about the biology of Cancer as it is about the sociology of biomedical practice and research.

A false dawn

Imatanib, the first drug of the age of personalized, precision cancer medicine, was a true game changer. With its introduction, a patient suffering from chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) could reasonably expect to live as long and be as healthy as somebody without the disease.1 Before imatinib, a sixty-five-year-old man diagnosed with CML was expected to live less than five years, compared with fifteen years for somebody without the disease. With imatinib, that man with CML enjoyed a life expectancy virtually identical to that if he had not developed CML.

But other genetically targeted drugs, while effective, don’t necessarily qualify as game changers. Such is the case with the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) inhibitor called crizotinib, which has been hailed as one of the biggest breakthroughs in genomic medicine of the last two decades. This drug has been proven to treat certain types of lung cancer (non-small-cell), but its benefits are limited. A recent meta-analysis of crizotinib found only scant evidence that the drug improved overall survival.2 A game changer? Debatable. In 2019, a single month’s worth of medication cost $19,589.30.3

Much of the low-hanging fruit of the genetics revolution had been plucked. More recently, developed drugs have offered diminishing returns. But despite this poor showing, researchers were slow to change course. Even as late as 2017, Dr. José Baselga, former physician in chief of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, one of the premier cancer hospitals of the United States, pleaded for more money to continue the drive for what he called “genome driven oncology.”4 “Cancer is a disease of the genome,” he stated baldly, desperately citing the now-ancient 1990s-era discovery of imatinib. Baselga himself was forced to step down in disgrace in 2018, when a New York Times investigation revealed that he had neglected to disclose financial conflicts of interest in a stunning 87 percent of articles he had written the previous year.5

The sexy idea of personalized, precision cancer treatment appeals widely to patients, physicians, and funding agencies alike.6 In 2015, President Barack Obama, unable to resist the siren song, dedicated millions more dollars to the Precision Medicine Initiative Cohort Program. Even by then, though, the evidence was overwhelming that genetics-based precision medicine could not fulfill its initial lofty promise.7

Personalized, precision cancer medicine depends upon two crucial steps: detecting the patient-specific genetic mutation, and delivering a targeted drug for that mutation. We’ve succeeded at step one, having identified thousands of gene variants, far more than we can possibly investigate. But what about step two? Could we actually deliver a drug to target that mutation? In 2015, only eighty-three of two thousand consecutive patients with complete genome testing treated at the specialty cancer hospital the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, in Houston, were eventually matched to a targeted treatment, representing a paltry 4 percent success rate.8

The National Cancer Institute fared no better in its Molecular Analysis for Therapy Choice (NCI-MATCH) trial.9 After mapping 795 cancer genomes, the NCI matched 2 percent to a targeted therapy—and not all those matched actually respond to treatment. Even at a highly optimistic response rate of 50 percent, this would constitute a 1 percent response rate to personalized cancer care, with an expected survival improvement measured in months. This was the state-of-the-art treatment in cancer genomic medicine in 2018, and it really sucked.

The poor results were not for lack of available medications. The Food and Drug Administration had been busy approving a cornucopia of new “genome-driven” cancer medications at an unprecedented pace. From 2006 to 2018, thirty-one new drugs for advanced or metastatic cancer were approved. Sounds pretty amazing. Almost three new drugs a year were being mainlined into the sickest cancer patients. Yet, despite so many new medications and the rapidly advancing technology of cancer genome sequencing, a 2018 study estimates that only a minuscule 4.9 percent of patients actually derived some benefit from genome-targeted treatment.10 Even after fifty years of intensive study, this paradigm of cancer fails more than 95 percent of people. Not good. How could so many “new” genomic medications deliver so few benefits?

One reason is that most “new” medicines are not new at all, but merely copycats of existing ones. Developing an innovative drug is hard work and carries substantial financial risk. Even highly effective drugs may fail due to unacceptable side effects. Copying existing drugs, rather than innovating new drugs, is a far more profitable strategy. If drug company A successfully develops a cancer drug that blocks gene target A, then at least five other drug companies will soon develop five other, almost identical drugs. To circumvent patent protection, they change a few molecules on a distant chemical side chain and call it a new drug. These copycat drugs carry almost no financial risk because they are virtually guaranteed to work.

Imagine that you sell children’s books. You could either write an original novel, or simply plagiarize the entire Harry Potter series but change the name of your hero to “Henry Potter.” Great novel? Yes. Makes money? Yes. Innovative? Not even a little. Hence the proliferation of drugs such as imatinib, nilotinib, and dasatinib, which are all basic variations on the same molecule. Instead of finding new genetic treatment, all those research dollars of the big pharmaceuticals just gave us some serious “more of the same.” Plagiarizing is a better corporate strategy than innovating. The benefits may be marginal, but the profits are maximal.

There are other ways to give the appearance of making progress. Of the many ways to game the system in medical research, using surrogate outcomes is one of the best.

Surrogate Outcomes

Surrogate outcomes are results that, by themselves, are meaningless, but they predict outcomes we actually do care about. The danger of trusting surrogate outcomes is that they don’t always reflect the desired outcome accurately. For example, two heart drugs (encainide and flecainide) were widely prescribed because they reduced extra heartbeats (called ventricular ectopy) after a heart attack, a surrogate outcome for sudden cardiac death. But a proper clinical trial proved that these two drugs significantly increased the risk of sudden death.11 The drugs weren’t saving patient lives; they were ending them.

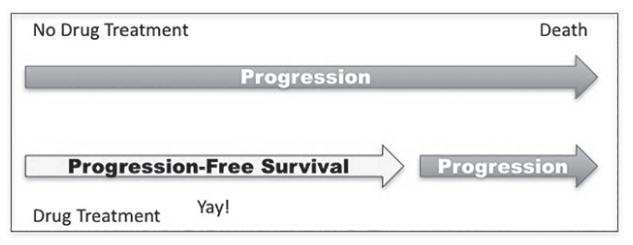

In cancer trials, progression-free survival (PFS) and response rate (RR) are two commonly used surrogates for the outcome we are most interested in, overall survival. PFS is measured as the time from treatment to disease progression, defined as a less than 20 percent increase in tumor size. Response rate (RR), in this scenario, would be the percentage of patients whose tumor shrinks more than 30 percent. In order to be useful, these surrogates must predict the clinical outcome—overall survival—but they don’t.12 The overwhelming majority of studies (82 percent) find the correlation between surrogate markers and overall survival to be low.13 Both PFS and RR are surrogate outcomes based entirely on reducing the size of a tumor, but surviving cancer depends almost entirely upon stopping metastasis, a fundamentally different beast (see Figure 9.1). Just because an outcome is easily measurable does not make it meaningful.

Illusion of benefit when outcomes are unchanged.

Size is only a single factor contributing to a tumor’s overall deadliness, and arguably, it is one of the least important. Cancer becomes more lethal when it mutates to become more aggressive or more likely to metastasize, and size-based surrogate outcomes like PFS and RR make little difference. Shrinking a tumor by 30 percent has virtually no effect on survival because of cancer’s uncanny ability to regrow.

Surgery is never done to remove 30 percent of the tumor mass, because that would be futile. Surgeons go to extraordinary lengths to make sure they “got it all,” because missing even a microscopic part of a tumor means that the cancer will definitely recur. While a minuscule 6 percent of drugs have reached this threshold of complete remission, from 2006 to 2018, fifty-nine oncology drugs were approved by the FDA on the basis of RR.

All these significant problems of using the cheaper but flawed surrogates for overall survival are well known. Before 1992, less than 3 percent of trials used surrogate outcomes. Then things changed. From 2009 to 2014, two thirds of FDA approvals came from trials using PFS as a surrogate outcome.14 For cancer drugs given the “breakthrough” designation, 96 percent relied on a surrogate end point.15 What happened?

In 1992, the FDA created an accelerated pathway that allowed approval based on surrogate outcomes. To compensate, drug manufacturers promised to conduct post-approval studies to confirm a drug’s benefit. Drug companies rushed to get drugs approved using these lowered goalposts,16 but confirmatory studies demonstrated that only 16 percent of drug approvals actually improved overall survival benefit. That means that 84 percent did not. If this were school, a 16 percent grade would not be an A or B, or even an F. It would be like submitting a term paper and receiving the grade H. It’s bad. Very bad.17

This reliance on surrogate outcomes has led to costly mistakes already. In 2008, the FDA approved the drug bevacizumab for metastatic breast cancer based on a 5.9-month improvement in PFS,18 even though overall survival was unchanged. Subsequent studies discovered reduced PFS, with no benefit to overall survival or quality of life, and substantial toxicity. The FDA withdrew approval for bevacizumab’s use in treating breast cancer in 2011.19

The cautionary tale provided by bevacizumab would be unheeded time and again. In 2012, the drug everolimus was approved for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer based primarily on surrogate outcome studies.20 By 2014, follow-up studies made clear that this drug provided no substantial benefits.21 In 2015, the drug palbociclib received approval for use in breast cancer, but once again, later studies failed to find any survival benefits.22 In the meantime, thousands of men and women suffered the devastation of holding out hope for a miracle cure, only to see it vanish before their eyes— their dreams of recovery slowly drained as surely as their bank accounts.

Surrogate outcomes allow earlier approval, which saves time. You would think this is a good thing for cancer patients, for whom time is precious. But how much time is actually saved? A modern cancer drug takes a median of 7.3 years to come to market,23 with 38 percent approved on the basis of RR and 34 percent on the basis of PFS. The use of surrogate outcomes generally saves an estimated total of eleven months of time. Is this time savings really worth an error rate of over 80 percent?

Five cancer drugs have already been approved through the accelerated program and then withdrawn when subsequent studies ultimately showed them to be useless. These drugs were marketed to a vulnerable public for 3.4 to 11.5 years.24 That’s shameful. Imagine that you sold your house to afford your cancer treatment, not knowing that the drug being hailed as the latest and greatest was literally useless. Worse, undergoing treatment with that drug meant that you weren’t able to receive treatments that might otherwise have had some benefit.

Despite the seventy-two “new” cancer medications approved between 2002 and 2014, the average drug extended life by only an average of 2.1 months.25 That’s only an average, and most drugs offered no survival benefits at all. The sobering reality of the poor performance of new cancer drugs26 is at striking odds with the public perception that the medical community is making leaps forward in the war against cancer.27 One study found that half the drugs hailed as “game changers” in the media hadn’t yet received FDA approval for use; 14 percent of these overhyped drugs had not even been tested in humans. Scientists have cured many thousands of rat cancers. Human cancers, though, not so much. Cancer research produces lots of publicity and excitement, but little actual advancement. Breakthroughs are heartbreakingly rare.

The ultimate goal of cancer treatment is to improve overall survival and quality of life. These patient-centered outcomes are hard to achieve and expensive to measure. To show benefits where none truly existed, you can politely move the goalposts by using surrogate end points.28 For a pharmaceutical company, a positive study means FDA approval, which means revenue. But many of the drugs in use are of limited effectiveness, so what is a pharmaceutical company left to do? Why, raise prices, of course!

Raising Prices

When it was launched in 2001, imatinib cost $26,400 per year. A steep price, to be sure, but it was truly a miracle drug and worth every penny. By 2003, its sales totaled $4.7 billion worldwide—a mega blockbuster generating huge, well-deserved returns for the drug developer. Prices (inflation adjusted) began to edge higher in 2005, rising by about 5 percent per year. By 2010, prices were soaring by 10 percent per year above inflation.29 Adding further to the bottom line, many, many more patients were living longer with their disease. This was a double bonanza for Big Pharma.

- More patients surviving CML = more customers.

- More customers + higher prices per patient = more money.

By 2016, a year’s worth of this miracle drug cost more than $120,000. By this time, the drug had already been on the market for fifteen years. That’s ancient history in medical science. It wasn’t cutting-edge stuff anymore; it was medical school stuff. The actual cost of manufacture, even after adding a 50 percent profit margin, is estimated at $216 a year.

When new competitors to imatinib emerged, prices should have dropped. But a strange thing happened: prices increased. Price competition is not nearly as profitable as price fixing and collusion, so prices continued their ascent into the stratosphere. Dasatinib, a copycat of imatinib, was priced higher than the drug it was trying to replace: it was an iPhone knockoff priced higher than a genuine iPhone.30 This exerted a strong pull on imatinib’s price: upward. Drug costs were limited only by what the payer (mostly the taxpayer) could bear.

Raising drug prices after launch is now commonplace. On average, inflation-adjusted prices rise 18 percent in the eight years after launch31 regardless of competition or efficacy. Imagine if Apple sold the original iPhone each year with no upgrades but raised the price annually by 18 percent—who would buy a new phone? No one. But cancer patients don’t have the luxury of making such a choice. As a result, price gouging is a routine part of today’s cancer landscape.

In the late 1990s, paclitaxel became the first blockbuster anticancer drug to reach $1 billion in sales.32 By 2017, a drug would need to rack up sales of $2.51 billion just to crack the top ten of oncology drugs.31 That is the reason that cancer medications took three of the top five spots on the list of the best- selling drugs of 2017.32

The top-selling drug of 2017 was Revlimid, a derivative of thalidomide, with sales of $8.19 billion. Such sales are easy to achieve when a drug costs in excess of $28,000 per month. Introduced in the late 1950s, thalidomide was notoriously prescribed for the treatment of morning sickness during pregnancy. Tragically, its use in pregnant women caused death and limb deformation in fetuses, and it was forced off the market in 1961. Thalidomide was reborn, though, in 1998, when it was approved for the treatment of leprosy and, more excitingly, multiple myeloma, a type of blood cancer.33

In the 1950s, the drug cost pennies. In 1998, the reborn thalidomide cost $6 per capsule. Only six years later, that price had risen almost fivefold, to $29 per capsule. The cost of making the drug is minuscule. In Brazil, a government lab sells it for $0.07 each.34 The average annual cost for a cancer drug prior to 2000 was less than $10,000. By 2005, this figure had reached between $30,000 and $50,000. In 2012, twelve of thirteen new cancer drugs approved were priced above $100,000 per year. That tenfold increase in twelve years is far in excess of reasonable.35

Combining the high prices of cancer medications with low efficacy means that the cost-effectiveness ratio is off-the-charts bad. A generally acceptable cost of one quality-adjusted life year (QALY) is $50,000.36 Cervical cancer screening has an estimated cost per QALY of less than $35,000.37 Imatinib was starting to push the limits, at $71,000. But regorafenib, used in the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer,38 costs a staggering $900,000 per QALY.

Price is a reasonable heuristic for quality for most consumer goods. Expensive stuff is generally of higher quality. Nike shoes are generally more expensive and of higher quality than dollar-store shoes. This does not apply to cancer medicine, where a high-priced drug does not necessarily work better than a cheaper drug. Many expensive drugs may not even work at all.39 This is obviously a big problem when drug costs are the single largest cause of personal bankruptcy in the United States.^[42]

Losing the War

Cancer paradigm 2.0 had hit rock bottom. Cancer was still undefeated, and the situation looked bleak. Millions of cancer research dollars over several decades produced an abundance of new drugs. Some are truly great, but most are marginally effective yet fantastically expensive. Benefits are borderline, toxicity is high, and cost is higher still. The drugs weren’t particularly useful, but they were particularly profitable. Lack of new drugs, the use of surrogate outcomes, and sky-high-but-still-rising prices: that’s how you lose the war on cancer. But the day is always darkest just before the dawn.

Notes

-

H. Bower et al., “Life Expectancy of Patients with Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Approaches the Life Expectancy of the General Population,” Journal of Clinical Oncology 34, no. 24 (August 20, 2016): 2851–57, doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.66.2866. ↩︎

-

J. Elliott et al., “ALK Inhibitors for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis,” PLoS One 19, no. 15 (February 19, 2020): e0229179, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229179. ↩︎

-

“Crizotinib,” GoodRx.com, https://www.goodrx.com/crizotinib. ↩︎

-

D. M. Hyman et al., “Implementing Genome-driven Oncology,” Cell 168, no. 4 (2017): 584–99. ↩︎

-

Charles Ornstein and Katie Thomas, “Top Cancer Researcher Fails to Disclose Corporate Financial Ties in Major Research Journals,” New York Times, September 8, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/08/health/jose-baselga-cancer-memorial-sloan-kettering.html. ↩︎

-

I. F. Tannock and J. A. Hickman, “Limits to Personalized Cancer Medicine,” New England Journal of Medicine 375 (2016): 1289–94. ↩︎

-

V. Prasad, “Perspective: The Precision Oncology Illusion,” Nature 537 (2016): S63. ↩︎

-

F. Meric-Bernstam et al., “Feasibility of Large-Scale Genomic Testing to Facilitate Enrollment onto Genomically Matched Clinical Trials,” Journal of Clinical Oncology 33, no. 25 (September 1, 2015): 2753–65. ↩︎

-

K. T. Flaherty, et al. “NCI-Molecular Analysis for Therapy Choice. Interim Analysis Results.” https://www.allianceforclinicaltrialsinoncology.org/main/cmsfile? cmsPath=/Public/Annual%20Meeting/files/CommunityOncology-NCI-Molecular%20Analysis.pdf. ↩︎

-

J. Marquart, E. Y. Chen, and V. Prasad, “Estimation of the Percentage of US Patients with Cancer Who Benefit from Genome-driven Oncology,” JAMA Oncology 4, no. 8 (2018): 1093–98. ↩︎

-

D. S. Echt et al., “Mortality and Morbidity in Patients Receiving Encainide, Flecanide, or Placebo: The Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial,” New England Journal of Medicine 324 (1991): 781– ↩︎

-

C. M. Booth and E. A. Eisenhauer, “Progression-free Survival: Meaningful or Simply Measurable?,” Journal of Clinical Oncology 30 (2012): 1030–33. ↩︎

-

V. Prasad et al., “A Systematic Review of Trial-Level Meta-Analyses Measuring the Strength of Association between Surrogate End-Points and Overall Survival in Oncology,” European Journal of Cancer 106 (2019): 196–211, doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.11.012; Prasad et al., “The Strength of Association between Surrogate End Points and Survival in Oncology: A Systematic Review of Trial-Level Meta-analyses,” JAMA Internal Medicine 175, no. 8 (2015): 1389–98, doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2829. ↩︎

-

R. Kemp and V. Prasad, “Surrogate Endpoints in Oncology: When Are They Acceptable for Regulatory and Clinical Decisions, and Are They Currently Overused?,” BMC Medicine 15, no. 1 (2017): 134. ↩︎

-

J. Puthumana et al., “Clinical Trial Evidence Supporting FDA Approval of Drugs Granted Breakthrough Therapy Designation,” JAMA 320, no. 3 (2018): 301–3. ↩︎

-

E. Y. Chen et al., “An Overview of Cancer Drugs Approved by the US Food and Drug Administration Based on the Surrogate End Point of Response Rate,” JAMA Internal Medicine, doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0583. ↩︎

-

B. Gyawali et al., “Assessment of the Clinical Benefit of Cancer Drugs Receiving Accelerated Approval,” JAMA Internal Medicine, doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0462. ↩︎

-

K. Miller et al., “Paclitaxel plus Bevacizumab versus Paclitaxel Alone for Metastatic Breast Cancer,” New England Journal of Medicine 357 (2007): 2666–76. ↩︎

-

R. B. D’Agostino Sr., “Changing End Points in Breast-Cancer Drug Approval: The Avastin Story,” New England Journal of Medicine 365, no. 2 (2011): e2. ↩︎

-

Roxanne Nelson, “FDA Approves Everolimus for Advanced Breast Cancer,” Medscape, July 20, 2012, https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/767862. ↩︎

-

M. Piccart et al., “Everolimus plus Exemestane for Hormone-Receptor-Positive, Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor-2-Negative Advanced Breast Cancer: Overall Survival Results from BOLERO-2,” Annals of Oncology 25, no. 12 (2014): 2357–62. ↩︎

-

V. Prasad et al., “The Strength of Association between Surrogate End Points and Survival in Oncology.” ↩︎

-

V. Prasad and S. Mailankody, “Research and Development Spending to Bring a Single Cancer Drug to Market and Revenues after Approval,” JAMA Internal Medicine 177, no. 11 (2017): 1569–75, doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.3601. ↩︎

-

E. Y. Chen et al., “Estimation of Study Time Reduction Using Surrogate End Points Rather than Overall Survival in Oncology Clinical Trials,” JAMA Internal Medicine 179, no. 5 (2019): doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.8351. ↩︎

-

T. Fojo et al., “Unintended Consequences of Expensive Cancer Therapeutics—The Pursuit of Marginal Indications and a Me-Too Mentality that Stifles Innovation and Creativity: The John Conley Lecture,” JAMA Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery 140, no. 12 (2014): 1225–36, doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2014.1570. ↩︎

-

D. K. Tayapongsak et al., “Use of Word ‘Unprecedented’ in the Media Coverage of Cancer Drugs: Do ‘Unprecedented’ Drugs Live Up to the Hype?,” Journal of Cancer Policy 14 (2017): 16–20. ↩︎

-

M. V. Abola and V. Prasad, “The Use of Superlatives in Cancer Research,” JAMA Oncology 2, no. 1 (2016): 139–41. ↩︎

-

T. Rupp and D. Zuckerman, “Quality of Life, Overall Survival, and Costs of Cancer Drugs Approved Based on Surrogate Endpoints,” JAMA Internal Medicine 177, no. 2 (2017): 276–77, doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7761. ↩︎

-

Carolyn Y. Johnson, “This Drug Is Defying a Rare Form of Leukemia—and It Keeps Getting Pricier,” Washington Post, March 9, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/this-drug-is- defying-a-rare-form-of-leukemia–and-it-keeps-getting-pricier/2016/03/09/4fff8102-c571-11e5-a4aa- f25866ba0dc6_story.html. ↩︎

-

Prasad and Mailankody, “Research and Development Spending to Bring a Single Cancer Drug to Market and Revenues After Approval,” 1569–75. ↩︎

-

https://www.igeahub.com/2018/05/28/10-best-selling-drugs-2018-oncology/. ↩︎

-

Alex Philippidis, “The Top 15 Best-Selling Drugs of 2017,” GEN, March 12, 2018, https://www.genengnews.com/the-lists/the-top-15-best-selling-drugs-of-2017/77901068. ↩︎

-

S. Singhal et al., “Antitumor Activity of Thalidomide in Refractory Multiple Myeloma,” New England Journal of Medicine 341, no. 21 (1999): 1565–71. ↩︎

-

Geeta Anand, “How Drug’s Rebirth as Treatment for Cancer Fueled Price Rises,” Wall Street Journal, November 15, 2004, https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB110047032850873523. ↩︎

-

Hagop Kantarjian et al., “High Cancer Drug Prices in the United States: Reasons and Proposed Solutions,” Journal of Oncology Practice 10, no. 4 (2014): e208–e211. ↩︎

-

P. J. Neumann et al., “Updating Cost-effectiveness: The Curious Resilience of the $50,000-per- QALY Threshold,” New England Journal of Medicine 371, no. 9 (August 2014): 28796–97, doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1405158. ↩︎

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Part V: Cost-Effectiveness Analysis,” Five-Part Webcast on Economic Evaluation, April 26, 2017, https://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/programs/spha/economic_evaluation/docs/podcast_v.pdf. ↩︎

-

D. A. Goldstein, “Cost-effectiveness Analysis of Regorafenib for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer,” Journal of Clinical Oncology 33, no. 32 (November 10, 2015): 3727–32, doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.9569. ↩︎

-

S. Mailankody and V. Prasad, “Five Years of Cancer Drug Approvals: Innovation, Efficacy, and Costs,” JAMA Oncology 1, no. 4 (2015): 539–40. ↩︎